Why is Ahmedabad 2021 above average, yet Brisbane 2022 is below average? This is why many of the flaws in the existing procedure would be eliminated if pitches were evaluated using technology.

Over the surfaces it is played on, no other sport is as obsessed with as cricket. Pitches are a topic of debate as well as a continual source of intrigue. Consider the Border-Gavaskar Trophy preliminary round, which features the customary dance of defensiveness and preemptive mistrust. Ian Healy extolled Australia’s chances, saying, “I think if they produce fair Indian wickets that are good batting wickets to begin with… we win.” A confident Ravi Shastri appealed for pitches that turned from the onset. I believe India outperforms us in those conditions if the wickets are unfair.”

Then in Nagpur, the covers came off and it became evident that the pitch had been mowed, rolled, and watered selectively. This “differential preparation” – which left bare patches outside the off stump of the left-handers on a spinner’s length at both ends – had presumably been designed to suit the home team, which had two left-arm spinners to the visitors’ none and one leftie in the top seven against four. The Australian players remained silent for strategic reasons, but was this going too far to give them the upper hand?

Even though match referee Andy Pycroft finally ruled that the pitch was not sanctionable, concerns over pitch preparation were once again sharply highlighted. Pitch-doctoring: could it become an even bigger temptation in the era of bilateral series, where World Test Championship points are at stake, as Rahul Dravid has noted? More generally, how is a “good” or “fair” pitch determined, and what exactly constitutes one?

The current operation of the ICC pitch-rating system

The ICC’s Pitch and Outfield Monitoring Process was first implemented in 2006 and revised in January 2018, with the stated goals being to better represent the range of global conditions, hold member boards more responsible for the pitches they generate, and increase transparency in pitch rating.

For every game, the pitch and outfield have the option of one of six possible ratings: very good, good, average, below average, poor, and unfit. The lowest three receive demerit points (1, 3 and 5 for the pitch, and 0, 2 and 5 for the outfield). If you accumulate five demerit points within a five-year rolling period, your ICC ground certification will be terminated for a full year. Pick ten, and there won’t be any international cricket for two years. Significantly important for the local association, maybe not as much for the national board. Before evaluating a pitch when it performs poorly, match referees are required to confer with the captains and umpires.

A pitch is considered “below average” when it has “either very little carry and/or bounce and/or more than occasional seam movement, or occasional variable (but not excessive or dangerous) bounce and/or occasional variable carry” . Okay, but how can you find this out?

Whether a pitch favors batters or bowlers, it is considered “poor” if it “does not allow an even contest between bat and ball”. The guidelines continue to point to “excessive seam movement” , “excessive unevenness of bounce” , “excessive assistance to spin bowlers, especially early in the match” along with “little or no seam movement or turn at any stage in the match together with no significant bounce or carry” in addition to “excessive dryness” along with “excessive moistness” . Okay, but how precisely do you figure all that out?

We learn that “Excessive means ‘too much'” from the comments for “clarification” in Appendix A of the ICC literature for the ratings. Yes, but how precisely do you quantify that?

Pitch marking leaves too much up to interpretation.

In actuality, pitches hardly ever receive any of the lowest three grades. Only six Test pitches out of 135 (plus one outfield) received a “below average” grade between the men’s World Cup in July 2019 and the end of 2022, with five of those pitches occurring in 2022. Rawalpindi had two “below average” ratings for 2022. The first came from Ranjan Madugalle during Australia’s March tour, which yielded 14 wickets for 1187 runs over the course of five days. The second was provided by Pycroft following England’s visit in December of last year, but it was later reversed on appeal. The appeal is now being heard by the general manager for cricket at the ICC, Wasim Khan, a former CEO of the Pakistan Cricket Board, and the chair of the cricket committee, Sourav Ganguly. How did they come to this conclusion?

“After reviewing the Test Match footage, the ICC appeal panel unanimously concluded that, although the Match Referee had followed the guidelines, there were several redeeming features – including the fact that a result was achieved following an exciting game, with 37 out of a possible 39 wickets being taken,” stated the official explanation. The appeal panel therefore came to the conclusion that the wicket was not deserving of the “below average” classification.”

This reasoning is strange. With just ten minutes of daylight remaining on the fifth evening, Ben Stokes’ team won with 921 runs at 6.73 runs per over, a historically unprecedented rate that “put time back into the game” and significantly increased the likelihood of wicket losses (every 43.2 balls compared to Pakistan’s 75.6). England’s plan was almost certainly developed after thinking about the March Test match against Australia. Is the ICC stating that if the Bazball method is used, this kind of pitch is suitable?

In an attempt to maintain transparency, the ICC would only cite the press release when asked how much of the match footage was examined.

An “average” pitch “lacks carry, and/or bounce, and/or occasional seam movement, but [is] consistent in carry and bounce,” per the pitch-ratings criteria. Okay, however consistency is a frequency-based attribute, and judging based on this suggests that in order to ascertain how frequently deliveries misbehaved, one would need to witness the entire game, or have access to the entire data set, much like a match referee would. Was the appeal panel responsible for this?

All of this leads to the feeling that the criteria for marking pitches contain too much “interpretative latitude” and, as a result, lack empirical robustness. This is supported by the fact that the decision made by an individual who watched the entire game (and, presumably, conferred with umpires and captains in accordance with ICC protocol) can be disagreed with by an individual who did not. This means that a match referee who has had a “below average” rating overturned on appeal is likely to play it safe the next time he has to choose between “average” and “below average,” if only because the criteria seem to support it. Why stick out one’s neck?

Following the return of the Rawalpindi appeal ruling in January, Pycroft played the first two Tests in the Border-Gavaskar series. The pitches in Delhi (a wicket every 38.8 deliveries, both sides playing three front-line spinners) and Nagpur (a “differentially prepared” strip where a wicket fell every 47.1 deliveries, though Australia only selected two front-line spinners, one of whom was a debutant) were both classified as “average”.

Chris Broad gave the third Test pitch in Indore, which features the same spin-bowling line-ups and a wicket every 38.5 deliveries, a “poor” rating at first, costing him three demerit points. The Ahmedabad bore draw’s strip, which had a 2.9 run rate reminiscent of the 1970s and a wicket that was lost per 115.7 deliveries over the course of five days on a hardly-changing surface, was classified as “average”. This was acceptable in light of the Rawalpindi decision, but it was undoubtedly unsuitable for Test cricket.

The Indore ruling was appealed by the BCCI, and Ganguly was forced to step down from the review process. Roger Harper was chosen as his stand-in. It didn’t really matter because the result remained the same: Wasim Khan and Harper “reviewed the footage” of the game and, although believing that Broad had “followed the guidelines,” concluded that “there was not enough excessive variable bounce to warrant the ‘poor’ rating.” Not sufficient. Alright, then.

As confusing as it all sounds, the BCCI clearly benefited from the outcome, though there are situations in which it might not have even been worth appealing – after all, the local association, which loses out on money and prestige, is the one being sanctioned, not the national board. And this is where there is room for abuse: Theoretically, vital games involving WTC points could be shifted to a nation’s second-class venues, with players instructed to fabricate biased pitches well aware of the possibility of receiving demerit points. The venue’s possible loss of ICC accreditation—taking one for the team, so to speak—would be fairly compensated by the board.

Why not enhance and add accuracy to the pitch-rating procedure using ball-tracking?

In the end, the subjective, interpretative component and the lack of empirical rigor in the pitch-ratings criteria do not help match referees—none of whom are allowed to voice their opinions about the system—and in certain cases, may even put them under excessive “political” pressure. They would presumably be in favor of an assessment methodology that is more fact-based and objective.

It may be the case that the ball-tracking technology, which has been an integral part of the infrastructure at all ICC matches since the DRS was implemented in November 2009, is the answer staring cricket in the face rather than impartial curators.

The pace, bounce, lateral deviation, consistency, and deterioration over time of a pitch are the performance attributes that match referees are essentially judging. Ball-tracking technology suppliers measure most of these already so they can use the data in their broadcasts. It is not beyond the realms of possible in terms of technology that these qualities may be given precisely calibrated parameters, pitches falling outside of which are deemed excessive, in order to get the various ratings.

The first step would be to go deeply into those more than 13 years of ball-tracking data (565 Tests and counting), figuring out the correlations between the various pitches’ quantifiable performance qualities and the scores they were given. Cricketing common sense would dictate that the facts and the decisions made by referees should have a reasonably logical set of correspondences.

You then begin to construct the parameters. Even though some of the variables should be easily “parameterized,” there would still be some complexity involved. Specifically: pace loss upon pitching, bounce, bounce consistency (and deterioration), and pace loss consistency throughout the game. Pitches that above specific levels will be sanctioned appropriately.

Although one would expect the deep dive to give excellent correspondences between pitch ratings and the ball-tracking data for sideways movement, lateral deviation, for both seam and spin, would be less accessible to parameterization and therefore more difficult to employ to develop a regulatory framework. Of course, deviation from pitching is instantly apparent, but bowler talent also has a significant impact. The revolutions the bowler imparts on the ball, the axis of rotation, the delivery rate, the angle of incidence with the pitch, and the age of the ball are among the many essential input variables that affect spinners and produce the degree of turn.

These variables may resist any one-size-fits-all parameterization because of their propensity for overlap and mutually reinforcing interactions. For example, once this is determined, a pitch may have “excessive” turn, but it may also turn very slowly with reasonably uniform bounce. In this case, the technology may be used to simulate the relationship between spinners’ degree of turn and pace loss, which would then be compared to widely accepted ideas of bat-ball balance.

Despite the difficulty of lateral deviation (where and how strictly to set the parameters?), a few points need to be made about it.

First off, everything here is within the reach of currently available technology, notwithstanding how challenging it may be to build the framework. (Hawk-Eye declined to comment on the possibility of utilizing its technology to evaluate pitch performance, whether for contractual or business reasons.)

Secondly, the objective is not to create an entirely prescriptive and flawless system, but rather to enhance the current one. Rather than being viewed as a flaw, the challenges in creating a comprehensive a priori model are only a reflection of complexity. Although they don’t stop all traffic accidents, seatbelt use is still preferable to not wearing one. Therefore, it may not be beneficial to automatically mark down a surface based on a predetermined degree of lateral deviation, even though it would be appropriate based on a precisely quantified pace loss after pitching. It would be necessary to balance additional considerations, but this would be done precisely with the help of the data the ball-tracking device gave.

Third, nothing will inevitably alter. These are heuristic instruments that enable a more rigorously scientific application of established criteria and values about the equilibrium of the game. But you would unavoidably boost match referees’ confidence in their assessments—especially in the face of irascible and influential national boards—by combining the quantitative (ball-tracking data) with the qualitative (the ICC’s pitch-ratings criteria descriptions). This would also increase public confidence in the process as a whole. Because of this, those 565 Tests might be considered a form of “legal precedent”: “Pitch X was marked ‘poor’ because, like Test Y in city Z, it exhibited an average of n degrees of lateral deviation for seamen’s full-pace deliveries on the first day.” Furthermore, as the teams’ on-field performance include elements of the game like intent, strategy, and skill that should be unrelated to the pitch-rating process, these decisions would be made regardless of how the teams performed.

Will the international game lose its diversity if pitches become more uniform due to the development of a technology-backed pitch marking framework? No. All that would have to happen is for the ball-tracking technology to define certain performance standards that a pitch would have to meet in order to be labeled as “average,” “good,” “very good,” and so forth. The question then shifts to how best to achieve those in any given context, which would also contribute to the body of knowledge regarding pitch preparation that might prove extremely helpful to the developing cricketing nations, where such expertise is not as prevalent.

Pitch-ratings methodology supported by technology would ease cultural issues.

Naturally, national teams’ boards would have no motive to “request” egregiously advantage-seeking pitches whenever it was convenient, whether for political, sporting, or other reasons, if punishments for poor surfaces affected them (by docking WTC points).

Less conspiratorially, creating a more accurate, data-supported framework will boost referees’ confidence in handling what is frequently a contentious political situation. This could be compared to the adoption of neutral umpires (or perhaps the DRS, which might eliminate the requirement that match officials be perceived as impartial).

And here’s likely the biggest, although least obvious, benefit of all: Most of the oxygen would be taken out of the cultural tensions that arise when pitch rates are discussed, the accusations and denials, the defensiveness and distrust. Defusing sensitivity would occur. In the era of social media, which have shown to be cutting edge antagonistic devices, this is not a minor issue. According to an old joke, 50% of respondents to a survey asking if society had become more divided replied that it had, and 50% disagreed.

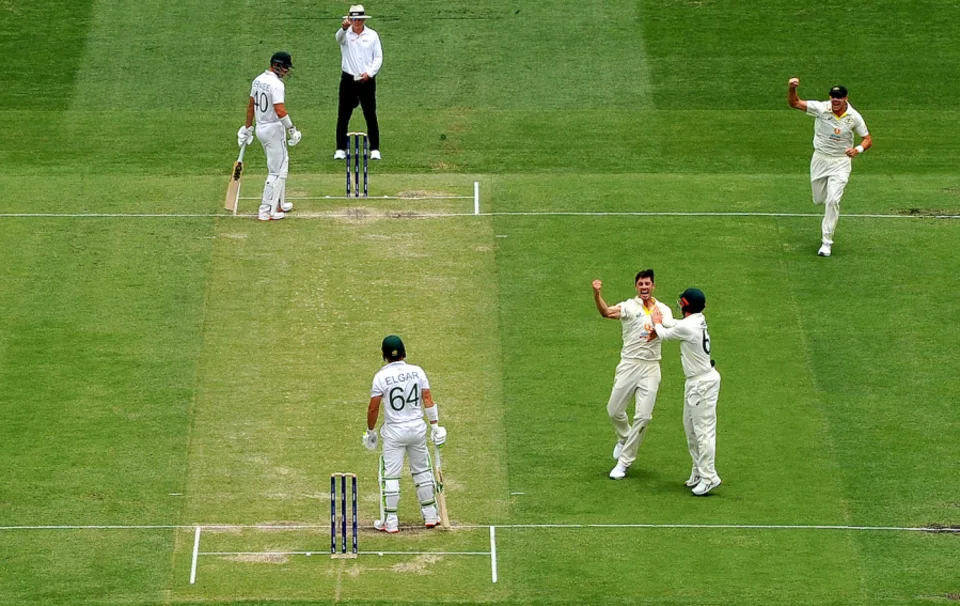

The most recent pitch to pick up a demerit point in Indore was the Australia-South Africa test played in Brisbane last December, which was finished in two days. This is an example of how these simmering concerns were sparked. The game’s nearly same length (particularly the way the overs are divided among the four innings) immediately drew comparisons from keen watchers to the day-night Ahmedabad Test match between India and England in February 2021.

A STORY OF TWO EXAMS

2021 AHMEDABAD AND 2022 BRISBANE

AHMEDABAD | BRISBANE |

|---|

| RUNS | OVERS | TOTAL | OVERS | |

| 1ST INNS | 112 | 48.4 | 152 | 48.2 |

| 2ND INNS | 145 | 53.2 | 218 | 50.3 |

| 3RD INNS | 81 | 30.4 | 99 | 37.4 |

| 4TH INNS | 49/0 | 7.4 | 35/4 | 7.5 |

The spirit of preemptive grievance and defensiveness set in before the Gabba pitch was even marked. Wasim Jaffer shared a meme on Twitter that compared the potential responses to a two-day pitch in the subcontinent and the SENA countries (South Africa, England, New Zealand, Australia). The meme basically implied that the cricket world would have been inconsolable if the two-day Brisbane outcome had occurred on an Indian surface. Though the concept of victimhood is fairly antiquated for Indian cricket in 2023, Jaffer was maybe comparable to the populist politician creating a straw man to stir up a sense of victimhood among his following (1.2 million Twitter followers currently) if social media is an anger amplifier.

To put it mildly, the responses would have been very different if the subcontinent test had ended in just two days. #AUS vs SA yvcH0rWweL – pic.twitter.com

@WasimJaffer14, Wasim Jaffer 18 December 2022

The irony, of course, is that while both sets of players and the curator agreed that Brisbane was “below average,” Richie Richardson rated Ahmedabad’s pitch, the shortest Test since 1935 (on which Joe Root took 5 for 8), “average” according to Javagal Srinath, who was serving as match referee because of Covid travel restrictions.

This is not meant to imply that Srinath is improper in any way. After all, he rated the Bengaluru Test pitch as “below average” a year later during a day-night encounter that lasted 223.2 overs. It is merely to highlight how any referee’s assessment of a pitch that is hovering between “average” and “below average” ratings may ultimately be a matter of perception, unconsciously influenced or conditioned by cultural background (“This isn’t a turner, mate!”), a point on which Jaffer is unintentionally correct. This is because of the interpretative latitude baked into the ICC’s pitch-ratings criteria.

Another reason in this situation is that, in general, pitches with excessive seam movement early in the game are not equal to those with excessive spin, even though the Gabba surface was initially very damp and consequently became pockmarked, causing varying bounce at speed as the surface baked. The former should theoretically get better as the game progresses. A pitch that is disintegrating and overly dry from the start will not improve. (However, there should be some leeway in the referee’s pitch rating to account for this expediency in cases where the umpires are eager to get the game underway in front of a packed stadium but the curator has prepared the pitch in wet conditions and is fully aware that it is excessively damp to begin with, fearing a demerit.)

A more impartial pitch-rating procedure would aid in preventing systemic abuse.

It is to be hoped that the International Criminal Court (ICC) is keen to use its existing resources to tighten all of this. In the end, however, there might be substantially more at stake than just calming cultural tensions or stopping WTC shenanigans. It may be in the interest of safeguarding the pitch-ratings procedure from potential misuse or even corruption to remove the potential pressure on referees to render the “correct” decisions in specific situations.

Think about the fictitious situation that follows. Six months before that nation hosts an ICC tournament in which the stadium has been designated to host multiple games, including the championship, a big stadium named for a firebrand populist leader finds itself on four demerit points. But before that, the facility hosts a high-profile Test match and creates another dubious surface, endangering its ICC accreditation. Owing to the fact that sport can be used as a tool of “soft power” for a regime, there would be tremendous pressure on the match referee in these situations because of the public interest in the rating given to the surface.

Or a hotter, more commercial version of the same situation. A ground perches on a suspension bridge on a Caribbean island. In addition to hosting games during the Under-19 World Cup, it will play host to 10,000 members of the Barmy Army during a Test match against England in a few months. In the event that a fifth demerit point was accumulated, the economy would suffer significantly. Once more, it is conceivable that local politicians would have a disproportionate amount of stake in the outcome of a potential U-19 World Cup match, based on the difference between a “average” and “below average” field rating.

Assuming a match referee is unaffected by external influences or the need to play it safe, which always grows whenever a pitch decision is overturned, a national board retains the ability to appeal and potentially wield influence. Why not play the dice and file an appeal, after all, if Pycroft can observe every ball of the Rawalpindi Test and have his well-considered assessment overturned by officials inferring the pitch’s characteristics from the scorecard, tail wagging dog? If administrators watched “footage” and decided whether the variable bounce was “excessive” or acceptable after Broad saw a ball in the first over of a game he witnessed in its entirety explode through the surface and rag square, then why not try to bend and stretch those utterly unscientific definitions to your advantage?

Both Rawalpindi and Indore demonstrate how urgently the pitch-ratings system needs more empirical weight and objectivity, if it is to avoid losing more confidence overall and keep match officials from being routinely hauled under the bus. Although the ICC claims to be satisfied with the current procedure, does its executive truly have the power to improve things, even in the event that they so choose?

The ICC executive’s ultimate lack of power in the face of the national boards, who are theoretically equal but may not be open to change regardless of whether it benefits the game, may ultimately be the obstacle to reform, as noted in the Woolf Report of 2012. To completely eliminate the prospect of some influential members engaging in some advantage-seeking skulduggery or pitch-doctoring may not be in their best interests. This is especially true for individuals who have an abundance of international venues and the ability to manipulate the system.

Under such conditions, the astute, careerist member of the ICC executive may conclude that it is best to avoid upsetting the big boys and to choose the least-excusing route. The ICC effectively becomes what Gideon Haigh called “an events management organisation that sends out ranking emails” in the absence of any meaningful regulatory bite in relation to bilateral cricket. Thus, inertia takes control and vagueness rules when it comes to marking pitches, which causes resentment to fester and ultimately results in cricket losing.